I once saw a squirrel try to climb a greased pole.

In fact, I see squirrels trying to climb greasy poles all the time. For example, I was recently working with a company that was struggling with a high turnover rate among its managers. As an engagement specialist, they brought me in to fix their retention issues.

They had a rigorous internal promotion process. Unfortunately, so many of the managers who started as stellar front-line sales people ended up flopping by the time they were promoted from salesperson, to sales manager, to department head.

The skills that made them successful as salespeople and managers didn’t translate well to department heads, which involved strategic planning, budgeting, and forecasting.

The business world might love the idea of promoting from within, but not everyone is meant to lead at every level.

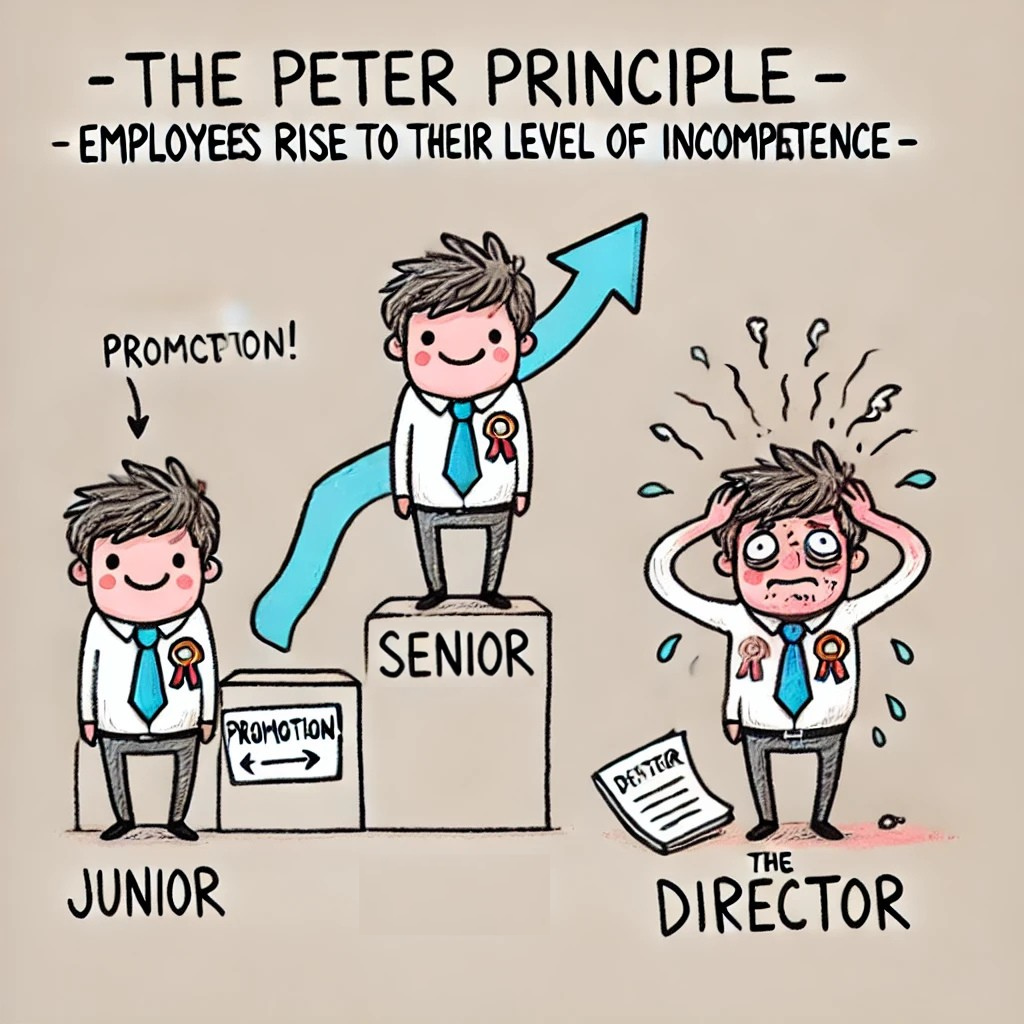

This is because of a concept called the Peter Principle.

The Peter Principle, in a nutshell, is the idea that people tend to get promoted to their level of incompetence. In other words, they get promoted based on their performance in their current role until they reach a position where they are no longer equipped to succeed.

It’s like that time I tried to bake a cake. I’m a pretty good cook, so I figured, “How hard can it be to bake?” Famous last words. Well, let’s just say it ended up looking more like a pancake than a cake. It was so flat, you could have mailed it with a postage stamp.

The same thing can happen in the workplace. Someone might be a fantastic salesperson, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll be a great manager or department head. Or someone might be a brilliant engineer, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be an effective leader.

In a study conducted by economists Alan Benson, Danielle Li, and Kelly Shue, which analyzed over 53,000 sales employees across 214 companies, it was found that high-performing salespeople were significantly more likely to be promoted to managerial positions. However, these promotions often led to declines in performance. The researchers concluded that “the most productive worker is not always the best candidate for manager.”

In Dance Floor Theory, we often say that a person’s job title doesn’t automatically equate to a Level 5 Leader on the DFT Engagement Pyramid. Someone can be an Executive and still be a 2, or a frontline worker and be a 5. The Peter Principle, through the lens of DFT, can be seen as promoting individuals based on their competence in one role without considering their overall contribution to the organization or their ability to grow and adapt to new challenges.

The Peter Principle can have serious consequences for organizations. It can lead to decreased productivity, low morale, and financial losses. It’s like having a whole team of squirrels trying to climb greased poles. It’s not going to end well.

According to a report by the National Bureau of Economic Research, organizations promoting employees based solely on prior performance can incur significant costs due to the resulting managerial incompetence. This highlights the financial implications of the Peter Principle

But here’s the good news: it’s avoidable.

In the context of Dance Floor Theory, the Peter Principle highlights the importance of recognizing and leveraging the diverse talents and motivations within a team. It’s not just about promoting the “highest performers” based on their current role but understanding their potential for growth and contribution in different positions.

Here are a few things organizations can do to avoid the Peter Principle:

- Identify the skills and competencies needed for each role. Don’t just promote people based on their past performance. Make sure they have the skills and abilities to succeed in the new role. In other words, don’t promote your star salesperson to manager just because they can sell ice to Eskimos. Make sure they can also lead a team, resolve conflicts, and make strategic decisions.

- Match current role skills with future role skills. Instead of just promoting someone because they excel at their current role, see if the skills that make them good now are what is needed for the promotion. If your salesperson is great at building relationships but terrible at paperwork, maybe don’t promote them to a role that requires a lot of administrative tasks.

- Track a person’s ability to learn new skills and grow over time. If you see a consistent ability to improve in new areas, that’s a positive sign they might not be affected by the Peter Principle. Look for employees who are eager to learn and take on new challenges. Those are the ones who are more likely to succeed in higher-level roles.

- Consider lateral moves. Sometimes, the best way for an employee to develop is to move laterally within the organization. This allows them to gain new skills and experiences without being promoted to a level where they might not be ready.

The Peter Principle is a real phenomenon, but it’s not inevitable. By taking steps to avoid it, organizations can create a more engaged, productive, and successful workforce.